This should have been a moment that Australia embraced with pride: one of the world's oldest continuous democracies finally recognising in its founding document that the vast continent it has helped shape into a modern nation is home to the world's oldest living culture.

Create a free account to read this article

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading

But we arrive at referendum day on Saturday, October 14, an anxious and divided country, the admirable hopes and ambitions of millions having collided with the understandable misgivings and mistrust of what most polls are tipping will be millions more.

Whatever the result, there will be endless opportunities ahead to rake over what might have been.

What might have been had Prime Minister Anthony Albanese channelled his evidently heartfelt commitment to the Uluru Statement from the Heart into legislating a Voice to Parliament first, building Indigenous and non-Indigenous understanding and consensus around its principles and purpose, before putting the constitutional question to the people.

What might have been had Coalition leader Peter Dutton and Mr Albanese both displayed a preparedness to pursue meaningful bipartisanship and do the hard graft of leadership: listening, persuading and negotiating to find common ground and shape the compromises that would give the referendum its best chance of being passed.

Instead, all-or-nothing Albo crashes into Dutton's No-alition and Australia finds itself split along the same old political fault lines. An important and potentially transformative conversation about the type of nation we want Australia to be and the best way to get there has degenerated into what at times has felt like just another two-tribes-go-to-war election campaign - with vitriol, derision and disrespect coming from both sides.

It's easy to see why many voters may be feeling resentful at being asked to take sides in a debate that the people we elect to lead have failed to help us navigate. Maybe it was always going to be an uncomfortable discussion for a population that's nowhere near match fit when it comes to referendums, and given the complexity of the social issues and history involved in this one.

But much of it feels like an argument we didn't need to have. The aspirations of both sides are not that far apart: no one is saying we should not be striving to improve the life expectancy and living conditions of Indigenous communities, especially those in remote areas, or that those Indigenous communities should not be as involved as possible in decision-making that affects them. Goodwill for this small but precious part of our multicultural melting pot and support for constitutional recognition of the long and proud history of Indigenous Australia runs deep and wide. And yet here we are torn down the middle, frustrated, disappointed and lamenting what might have been.

But none of that matters now. What matters now is whether you believe the specific proposal being put forward on your referendum ballot paper will advance Australia fairly. Does it have the potential to make our successful democracy, and the lives of our Indigenous people, better?

Your ballot paper is not seeking your endorsement for a person or a party or a slogan. What's on your ballot paper is an idea called the Voice.

The idea came from a significant group of Indigenous leaders who met at the foot of Uluru in Central Australia in 2017 to consider ways Australia could formally recognise its Indigenous population in the constitution. Through their Uluru Statement from the Heart, the group proposed that constitutional recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders "as the First Peoples of Australia" could be achieved by establishing a Voice to Parliament that would give them active and ongoing input when laws and policies that affect their lives were being devised and enacted.

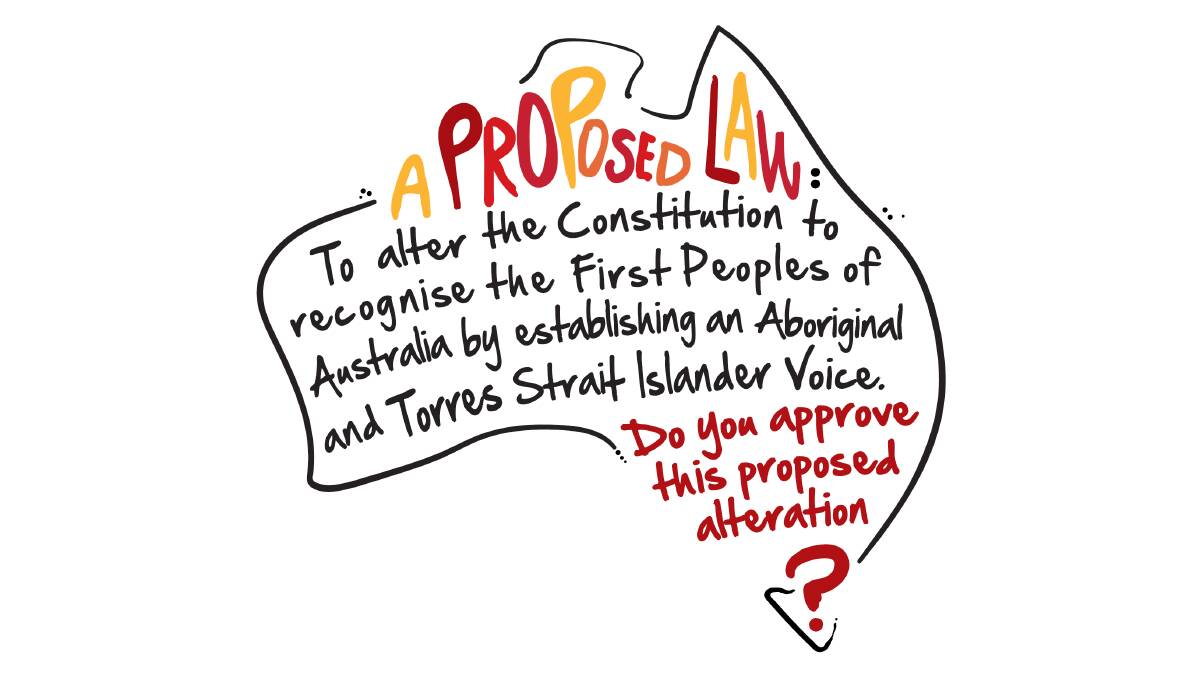

Your ballot paper puts the question plainly: "A Proposed Law: to alter the Constitution to recognise the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice. Do you approve this proposed alteration?"

Whether you write "yes" or "no" on your ballot paper, there are valid arguments and anxieties on both sides. There are uncertainties and different potential consequences with either choice.

Yes, we need our constitution, which is effectively silent about the first inhabitants of this land, to evolve to acknowledge and embrace the oldest continuous culture on the planet. Do we want that formal recognition to be merely a symbolic nod to the past or a real and practical change that supports this unique culture with its unique challenges into the future?

Yes, a committee of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, chosen by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, providing advice to parliament and the executive government could contribute to better decisions. On average Indigenous Australians live eight years less than other Australians. The suicide rate is two and a half times higher. One in two live below the poverty line. The unemployment rate is up to nine times higher. And an Indigenous boy is more likely to go to jail than to university. By informing the parliament as well as ministers and the public service about how to implement policies that work with Aboriginal culture and practice, the Voice has the potential to give Indigenous communities greater responsibility for closing these gaps.

No, the Voice proposal is not a simple or modest change as Mr Albanese has tried to present it. It creates a new chapter of the constitution and fundamentally alters the way Australian democracy works. Yes, parliaments would retain supremacy, decide the body's form and function and choose to ignore or accept its advice, but the Voice has been purposefully designed to exist in perpetuity - beyond the reach of the government of the day to extinguish it. The 1999 republic referendum may have proposed 69 changes to the constitution where this by contrast proposes to add only about 100 words. But even former High Court chief justice Robert French, who has hailed the Voice as "a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for Australia to fill a gaping hole in our constitution", describes it as a "significant institution in our representative democracy". Is that the change we need and want?

Yes, the proposed model can be viewed as dividing Australians. Because the Voice would comprise only Indigenous Australians chosen by Indigenous Australians advising on matters that concern Indigenous Australians, it is by design treating one group of us differently based on ancestry. It's probably more accurate to say the Voice is about indigeneity than race. Australia is made up of people of many races but it has only one Indigenous peoples and because of their unique history of dispossession and generations of ensuing disadvantage they are asking for unique recognition and redress via the Voice.

Which brings us to what appears to be the sticking point for many Australians. Dividing people by indigeneity, even with the very best of intentions, still divides Australian citizens into two groups with different constitutional rights. It's the argument that has been articulated most powerfully by Senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price and Nyunggai Warren Mundine, leaders with Indigenous heritage who reject the Voice as a move away from national unity and equality of citizenship under the constitution, and a measure that entrenches the notion that the settlement of Australia was fundamentally unjust.

And yet a colleague of their same political stripe, Liberal MP Julian Leeser, Senator Price's predecessor as shadow minister for Indigenous Australians, sees the Voice very differently. He calls it an opportunity for us to add a new chapter of empathy and practical progress to the three-part Australian story of Indigenous heritage, British constitutional democracy and multiculturalism: "Empowerment, partnership, respect and the strengthening of Indigenous civic infrastructure, this is how the Voice brings change".

The Uluru Statement from the Heart does not disguise these aspirations and ambitions for Indigenous Australians: "We seek constitutional reforms to empower our people and take a rightful place in our own country. When we have power over our destiny our children will flourish. They will walk in two worlds and their culture will be a gift to their country".

That's why this is a decision of consequence for Australia. The proposal before us is imperfect. But it does, on balance, present an opportunity many of us may not see in our lifetimes to make our country stronger by taking a meaningful step towards reconciling our past and improving the future for Indigenous Australia. It promises a moment of national pride - a moment we tell our children and grandchildren about - and that's precisely because it is a big idea and a bold one. But it is not without uncertainty and potential complications.

No change is. And no change of this political and cultural and historical significance is "safe change" - not in the era of polarised politics and toxic social media and Brexit and Trump. So voting "no" does not make you racist or ignorant, certainly not if you've done your homework and you believe your questions have not been adequately answered. Equally, voting "yes" because you want to recognise our First Peoples in a profound way that seeks to address racism and disadvantage does not make you a woke idealist.

It might be hard for devout believers on either side to contemplate, but whether Australia ends up voting "yes" or "no", we will have made the decision that is a reflection of Australia on this particular idea at this particular time. And despite the fears held on both sides, Australia on October 15 will still be, as the national anthem now appropriately acclaims, "one and free". As the opening line of our constitution declares, the people "have agreed to unite in one indissoluble Federal Commonwealth" - that is the enduring national achievement we must continue to cherish and strive as citizens to sustain.

- Responsibility for this referendum comment is taken by ACM executive editor James Joyce of 121 Marcus Clarke Street, Canberra.